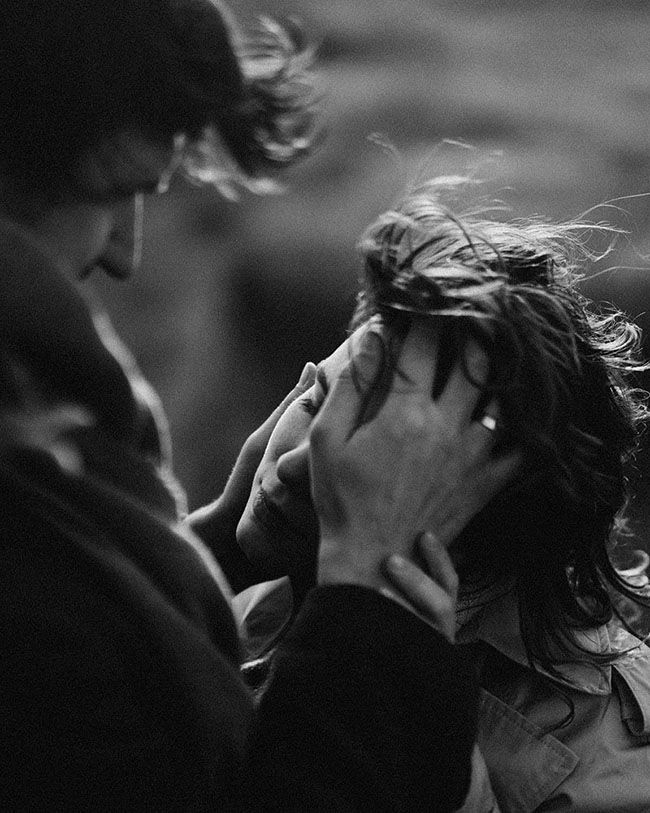

Image: @maleyphoto

It was Gandhi that remarked on the human species’ nasty habit of believing that we alone are right, and the others are wrong. And there is nothing new about that thought. The ancient Greek Stoics remarked on the way we attribute qualities to others, interpret their behaviour and make erroneous deductions based on these very qualities. We would rather be disappointed in people than rethink our opinions, even if they were baseless in the first place.

Today, sociology reaffirms the reckonings of such historic thinkers. We could all do with mastering the art of dialogue. This way we can interact with living human beings, who have nothing to do with the labels that we tend to mindlessly attribute to them. So how does one go about it and why does not it happen naturally?

The habit of labelling is only natural to humans. In an attempt to find a shortcut, rather than spend time analysing and weighing up the pros and cons, we tend to jump to conclusions, which require less effort on our behalf and - let’s be honest -typically serve our own interests. Say, your colleague is late, you will likely assume that they are a bit of a disorganised slacker. But had the roles been reversed, you would likely have a flurry of reasons for being late such as terrible traffic, a faulty alarm clock and a dire weather to top it all off!

The Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider was the first to seriously address the way people evaluate the actions and motivations of others back in mid-20th century. According to him, there are two types of judgements: internal and external. The former is influenced by our personal qualities, the latter – by external circumstances beyond our control. Lee Ross, the professor of psychology at Stanford University, formulated a postulate based on this very classification. It became known as the “fundamental attribution error”.

As the famous Biblical idiom goes: “First get rid of the log in your own eye; then you will see well enough to deal with the speck in your friend's eye.” In a nutshell, we are naturally prone to blaming the external circumstances when it comes to adversity that happens to ourselves and attribute it to internal personal qualities when it comes to others.

By assigning certain characteristics to others, we convince ourselves that if someone is kind they will remain so forever, without taking into account the possible mood changes or even bad weather. We assume that bad things happen to us due to external circumstances and happen to others because it is their own fault. This way of thinking flips, when it comes to success: others have just been lucky, while I busted my gut to get there. Needless to say, this simplified view of the world does not do us any good. As much as we might try and pigeonhole others into specific categories, the chances are they simply will not fit in.

What is the first thought that crosses your mind, when a friend cancels on lunch last minute without an excuse? There are likely a couple of options. The first being “she/he must have a good reason”. The second being “What, again? She/he is so unreliable”. If the founder of the attribution theory Lee Ross was to join your pity party on this unfortunate occasion, he would probably politely note that your friend is motivated by both external and internal circumstances.

The same can be said of your reaction to this mishap. It can depend on your overall stress levels at the time, on how comfortable you might be with sitting alone in a café or just on how much you were looking forward to catching up with your friend. Not to mention starting the day off the wrong foot with a burnt toast and that it was pouring down this morning.

It is likely that your friend has an equally sizeable list of reasons. Perhaps, some trouble at home that might be too awkward to share, health issues (it can even be an anxiety attack or an onset of depression), a sudden need to be alone or a whole bunch of other reasons you might not be privy to. Note that all of these are external circumstances, rather than personal characteristics.

At first, the fundamental attribution error can seem trivial and not worthy of our attention. After all, get by when it comes to maintaining relationships on a daily basis. But an average person deals with a myriad of conflicts of different kind, scale and impact. It can take the form of troubles at work, a lack of understanding at home or an inability to accept social norms of some kind. Then there is the element of internal conflicts, which can influence all spheres of life.

By relying on labels and categorising others we are bound to face the consequences. Nuances are easily missed, misunderstandings develop and the whole strategy around your interaction is undermined as a result. This can in turn lead to arguments with loved ones, missed career opportunities and pointless grudges.

Goethe once wrote that “a person hears only what they understand”. But the limits of your understanding can be pushed. Learning to correctly interpret the behaviour of others is a critically important skill, which will help you regain control of your nervous system and keep your relationships with others secure.

Rule 1: think of yourself first

“For I underestimate myself, and that itself means an overestimation of others,” wrote Franz Kafka. Indeed, our deductions about other people are intertwined with the way we relate to ourselves. A realisation of the fact that we do not always view ourselves fairly can be a great starting point in moving towards a closer understanding of others.

Buddhists believe that we understand others because we understand ourselves. By looking inwards, we become conscious of the illusionary self and of our own weaknesses. It helps us understand our own human nature, learn to love and to forgive. Simple embodiment practices such as meditation and journaling can help with achieving this state.

Rule 2: think of the consequences

The Buddhist idea of karma states that we are responsible for our own actions and experience their consequences. The Christian metaphor “you reap what you sow” echoes this. Whatever it is you do, it is worth realising what the consequences of your actions might be. When it comes to dealing with people, who are flesh and blood, these consequences can backfire in the form of grudges, lost trust or a favour gone wrong. It is much more rational to pre-empt such scenarios from happening in the first place rather than to have to deal with their aftermath.

An ability to grasp a simple cause and effect chain is a mental exercise that can be mastered. In envisioning clear consequences of your words and actions, you can adjust your behaviour accordingly and not give in to emotions. This means analysing whether your words will achieve what you want before exploding in rage or snapping at another person. By pursuing the latter, you will likely achieve the opposite effect.

Rule 3: treat socialising as an art

A truly compassionate, understanding and warm interaction is as much of an art form as writing a novel, painting a picture or composing a beautiful melody. As with art, socialising requires effort to achieve that one masterpiece. This implies having the ability to listen, clearly formulate your thoughts and not rush to conclusions.