Clothes don’t make the (wo)man, but they certainly make the first impression. Whether it is an interview, a business dinner or a first date, clothes are perhaps one of the first things that women think about. We carefully choose an outfit that would make the best impact. And there is more to it than wanting to look good. It is also about the power of fashion.

Clothes are not just a means of self-expression but also an important element of an image we project. Our fashion choices can be a reflection of a unique sense of style or even a political statement. What do the suffragettes’ white frocks have in common with the little black dress of the Golden Globe’s red carpets? Where does the concept of power dressing even come from and what forms does it take on today? We will be taking a brief dive into the significance of clothes in the women’s rights movement.

An era of strong women

The idea of power dressing might not be an obvious one to the new generation of women, if not altogether unfamiliar. It is best known to those whose youth falls on the 80s. The mere mention of this term would likely bring up images of rebellious young women determined to dismantle the stereotypes regarding female purpose and taking up office jobs around the world by storm.

For a woman getting a senior role in politics or business at the time was no easy feat. An area dominated by men since times immemorial, it forced women to play the game by their own rules. Without much thought, young career driven women turned to one of their main and most reliable weapons – fashion. This is how a classic business lady’s outfit became a clone of the male wardrobe.

Pantsuits, long jackets with broad shoulders and below-the-knee skirts were designed to hide the curves of the female figure. Meanwhile, minimalist jewellery and formal hairstyles were used to highlight the professionalism of female candidates. Overly romantic and complex prints were pushed out by stripes and pied-de-poule, or houndstooth, pattern, bright colours were replaced by muted blues, blacks and greys.

The Iron Lady’s style

Margaret Thatcher became a role model for many ambitious women. Whether you agree with her political views or not, her influence is unquestionable. A grocer’s daughter and the first female Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, she knew all about the challenges of gaining respect and attention in an environment dominated by men.

In order to fulfil her goals, the Iron Lady had to ditch her much loved quirky hats, dye her hair to a more discreet shade of blonde and take a lot of coaching for her naturally high-pitched voice. No one compares to her when it comes to power dressing and using the language of fashion.

Thatcher’s two classic looks are a mini dress paired with a coat and a two-piece suit with a blouse. Margaret had a traditional approach to colours and usually preferred different shades of blue. This choice was not dictated by the colour of her eyes but had a symbolic meaning. Blue is the colour of the conservative party, which she represented.

United in colour

The idea to convey ideology through fashion was not just a remit of the Iron Lady. The tradition of attributing a hidden meaning to the clothes’ colour was not new and often came hand in hand with protest movements. Since the time of the French Revolution, people demonstrated their political views through clothing. Monarchists picked lighter or green colours, while their counterparts opted for the white/blue/red tricolour.

The feminist movement gained momentum in the 20th century. Women, who demanded equality of electoral rights, picked green, purple and white as their colours. They symbolised hope, chivalry and purity respectively. It was white garments that defined the dress code of the suffragettes, who wore it to their public initiatives.

In 1908, more than 300,000 women gathered together at a meeting in London’s Hyde Park to fight for their civil rights. With all of them wearing white, they were impossible not to notice. The political and social shifts of today continue to use visual codes. Be it the pink pussyhats at the Unites States 2017 Women’s March, France’s yellow vest protests or women wearing all black at the 2018 Golden Globe as a symbol of their fight against sexual misconduct in Hollywood.

From bloomers to tuxedos

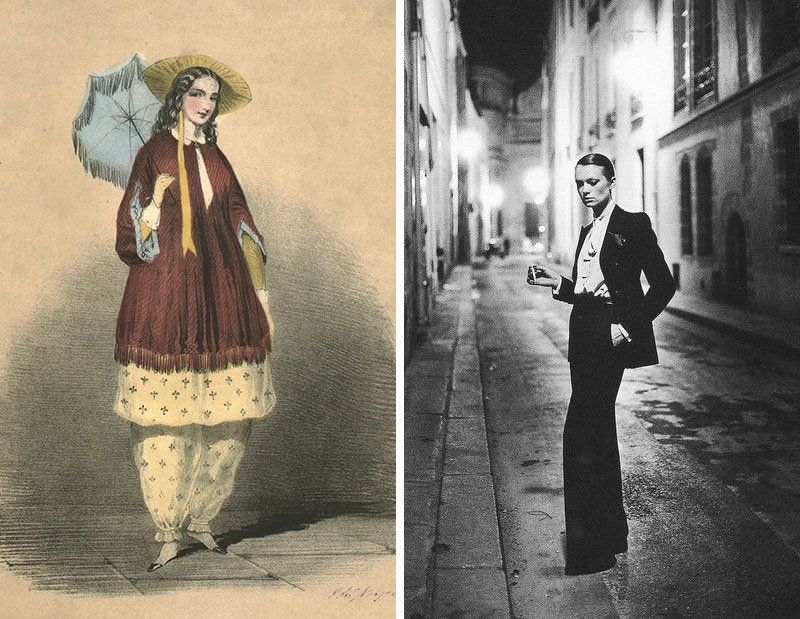

The story of a powerful woman’s uniform would not be told in full if we did not touch on trousers, namely their long and painful journey into the women’s wardrobe. The mother of the “trouser revolution” was Amelia Bloomer, a suffragette and a founder and editor of the first ever newspaper for women.

In 1850, she turned up to her own lecture in a short and rather wide skirt, combined with pantaloons, tied with a lace at the ankles. This unthinkable attire at the time was a scandal and a cause of much public mockery. But there were also others, who flooded the activist with letters requesting that she shares her how-tos for making the first pair of female trousers. This is how the fashion term bloomers came about. The demand for this garment was a vivid illustration of how fed up women were of wearing heavy floor length skirts.

Rapid changes in women’s fashion began to take hold during the First World War. As women started to take on some of the typically male responsibilities, they were permitted to work in manufacturing where they wore trousers and jumpsuits. Soon Coco Chanel was making waves in France and was particularly keen on items affiliated with a male wardrobe. Then came the age of the famous cinema stars Marlene Dietrich and Katharine Hepburn who wore suits in their screen appearances.

But the main trendsetter for adopting male fashion for women was Yves Saint-Laurent. In 1966, the French fashion designer presented the first female tuxedo. The majority of the audience has not taken a liking to the maestro’s latest creation and those who braved the suit were soon met with more criticism. As the story goes, in 1968 famous socialite Nan Kempner was almost kicked out from New York’s La Côte Basque restaurant for being dressed “inappropriately” in a YSL tuxedo. Undeterred, Saint-Laurent’s muse ditched the trousers and proceeded to the table wearing nothing more than a jacket.

The uniform of power

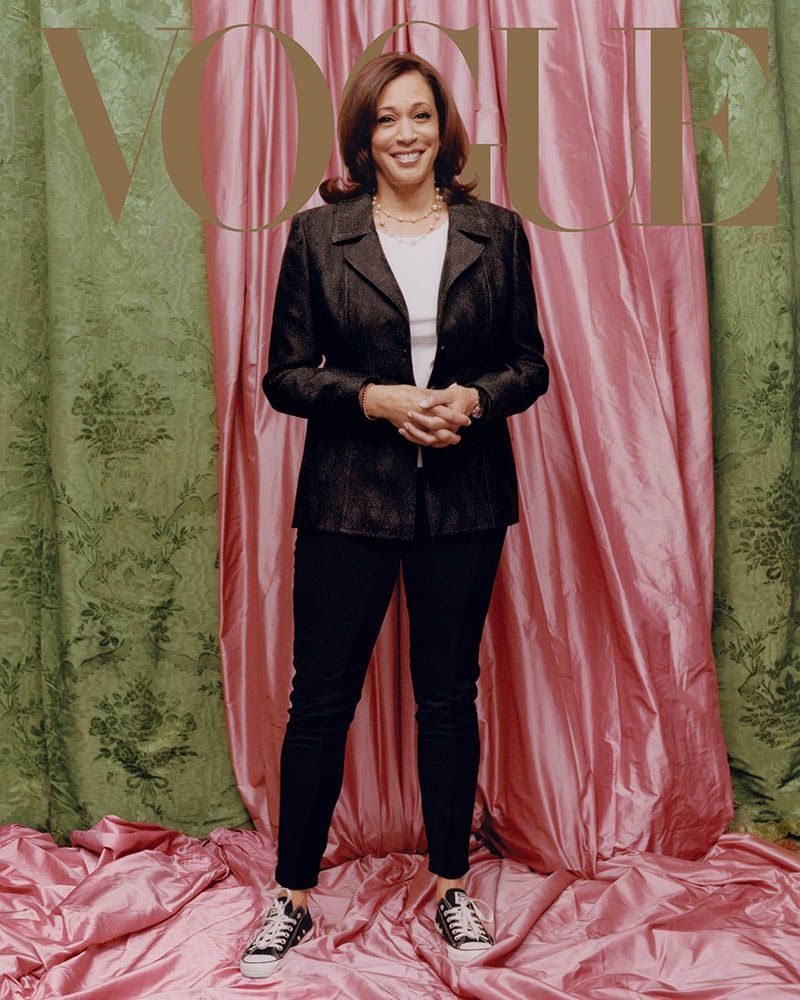

Today, women’s tuxedo is a classic of professional fashion. Take the unchanging trouser suits of Angela Merkel, who has been leading the rankings of the world’s most powerful women year after year or Hillary Clinton’s outfits throughout the various stages of her career. Let us not forget that power dressing is not just about rigid masculine silhouettes, but about daring to be yourself. There is no better example of it than the Vice President of the Unites States Kamala Harris.

The first woman in this important role, she started a new page in the history of fashion as a symbol of female power and strength. Kamala’s now signature look consists of a pantsuit, white T-shirt, pearl necklace and a pair of Converse sneakers. Black and white, the platform kind and the flat kind, the kind that lace, the kind that do not lace, Harris has an impressive collection of trainers. She wears it in her daily life and at work, hence setting a new standard for what a powerful woman should look like.